Your mom

probably told you long ago that it’s what’s on the inside that counts. Nothing could be closer to the truth when it

comes to training your abdominals. That

may sound a bit strange considering that most people looking to firm and sculpt

their abdominals spend hours each day crunching away at the gym with visions of

tight, flat, tummies dancing in their heads.

To understand how to effectively train your abdominals for optimum

spinal health as well as to get the look you desire, we’ve got to explore the

abdominal anatomy from the inside out.

There are four layers of abdominal muscles:

- Transverse abdominis

- Internal obliques

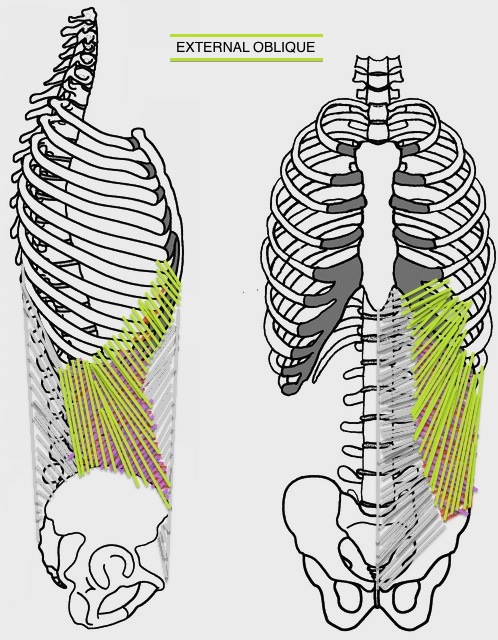

- External obliques

- Rectus abdominis

Transverse Abdominis is

the deepest layer of abdominal muscle.

It functions as your body’s corset, supporting the contents of the

abdominal cavity and providing spinal stability. This muscle originates on the iliac crest

(top of the pelvis), the lower six ribs, and the sheath of connective tissue

that covers the deep muscles of the back and trunk (thoracolumbar fascia).

The transverse abdominis is a muscle of stability, not of

movement. Beginning in the late 1980’s,

the use of imaging techniques to directly measure the activity of this muscle

has allowed more insight into the role of transverse abdominis in spinal

stabilization.

Transverse abdominis activates subconsciously in

anticipation of trunk and limb movement.

Unlike the other abdominal layers, transverse abdominis is recruited

continuously regardless of the direction of movement. Contraction of this muscle reduces the

circumference of the abdominals (flattening you from the front and slimming you

from the sides). This circumferential

contraction (with the aid of the pelvic floor and diaphragm muscles) creates an

air-bag effect providing support and stability to your spine. Studies have shown that, in people

with back pain, contraction of transverse abdominis is often delayed, disturbed, and

sometimes completely absent.

How to access and

train your transverse abdominis:

To find your transverse abdominis, hook your fingers on the

bony protuberances on the front of your pelvis (your “hip bones”) and imagine

pulling a drawstring tight from hip bone to hip bone … you should feel this muscle engage laterally across the front of your pelvis.

Once you've located the muscle, dead bug is a great exercise to help you isolate and

strengthen it.

Begin lying flat on your back, knees bent, feet hip distance

apart and spine and pelvis in neutral. (In

neutral spine you maintain the natural curvatures of your spine. In neutral pelvis your “hip bones” should be

in the same vertical plane as your pubic bone).

Engage your pelvic floor muscles, engage transverse abdominis, and

bring your knees over your hips while reaching your arms for the ceiling. Slowly move one leg forward while reaching

the opposite arm back. You will use your

transverse abdominis to prevent any movement in the spine or pelvis. If this proves too challenging, you can place your arms and/or one foot on the floor.

If you are having trouble feeling the contraction of

transverse abdominis, give yourself as much sensory feedback as possible. Place a hand on your abdominals to provide

tactile feedback and/or perform the exercise in front of a mirror to give

yourself visual feedback as to the stillness of your spine and pelvis.

CLICK HERE for a nice video link of a physical therapist demonstrating the dead bug exercise.

CLICK HERE for a nice video link of a physical therapist demonstrating the dead bug exercise.

The remaining layers of abdominal muscles are involved in

movement of the trunk. Your trunk &

spine can move in a multitude of directions including flexion, extension,

lateral bending and rotation. The deep and superficial back muscles work with

the abdominal muscles to create trunk movement.

TRUNK MOVEMENT

|

MUSCLES USED

|

Flexion

|

Rectus abdominis,

internal & external obliques, psoas

|

Extension

|

Erector spinae,

quadratus lumborum, lower trapezius, interspinalis

|

Lateral bending

|

Quadratus lumborum,

internal and external obliques, transverse abdominis, intertransverse

|

Rotation

|

Internal &

external obliques, erector spinae, quadratus lumborum, transverse abdominis,

multifidus, rotatores, psoas

|

To keep things simple, you can take the same dead bug

exercise described above and layer on work for your oblique muscles and rectus

abdominis. Be sure that you've mastered the basic exercise described earlier before adding on these variations.

From the same starting position (knees over hips, arms

reaching for the ceiling), use your oblique muscles to create a posterior

pelvic tilt (lifting the front of your pelvis toward your low ribs, pressing

your lower back in to the floor). Now

challenge the contraction in the same way you did in the first exercise

(opposite leg and arm reaching away from each other). You may find you have

greater range of motion in the exercise now that you’ve added another layer of

abdominal contraction.

Finally, add a challenge for the outer layer of abdominals

by straightening your legs over your hips, then, keeping your low back on the

floor slowly reach both legs away from you (this

provides an eccentric contraction for the outer layer of abdominal muscle –

lengthening the muscles while they contract). Bring your legs back in over your heart and

roll your tailbone and sacrum up off the floor (be sure to keep your shoulders

firmly on the floor – use only your abdominals!).

Remember to start from the inside out in any abdominal

exercise that you choose to perform.

Find stability from your deepest layer of abdominal muscles and then add

movement to train the outer layers.

The result will be the winning combination of firm, flat abdominals

& a happy, healthy spine!

References:

References: