Which muscles first come to your mind when thinking about

core stability? For many people the

abdominals are synonymous with the core.

Although the abdominals are certainly part of the puzzle, in order to

improve athleticism and prevent injury, many more pieces are needed.

One really great description of the core is a “ … muscular box with the abdominals in the

front, paraspinals and gluteals in the back, the diaphragm as the roof, and the

pelvic floor and hip girdle musculature as the bottom” (Akuthota, Ferreiro

& Fredericson, 2007).

I covered the abdominals in my last post

“Your Abdominals from the Inside Out”. This post will

expand on the core musculature by focusing on the hips and pelvic girdle. The pelvic girdle holds a position of critical

importance when it comes to the kinetic chain.

It is common to see reference to the “lower kinetic chain” (foot, ankle,

knee & lumbopelvic hip girdle) and the “upper kinetic chain” (lumbopelvic

hip girdle, spine, shoulder, elbow, hand). The hips and pelvis are the important center

link of this chain and play a crucial role in stabilizing the trunk and pelvis

in movement and in transfer of force between the upper and lower body.

If you’ve ever watched a professional baseball player, tennis

player or golfer you know that it really is all

in the hips! Optimal flexibility and

strength in the muscles that support the hips & pelvis coupled with body

awareness and endurance is a winning combination for injury prevention and

success in any sport.

The bones of the hip joint and pelvic girdle include the

three fused bones of the pelvis (ilium, ishcium, pubis), the sacrum (which is

actually 5 fused vertebrae at the base of the spine), and the femur.

The joints include the symphysis

pubis (where the two pubic bones come together at the front of the pelvis),

the two sacroiliac joints (where the

sacrum comes together with the ilium at the back of the pelvis), and the hip joint. The hip joint is a ball and socket

joint. The “ball” is the head of the

femur bone. The “socket” is called the

acetabulum and is formed by all three of the pelvic bones (ilium, ischium &

pubis).

The first two joints, symphysis pubis & sacroiliac, have

very little movement. The third, the hip

joint, allows for movement in a variety of planes. The muscles that move the hip joint can be

divided into the following categories:

Hip Flexors Hip

Extensors

Psoas Gluteus

maximus

Iliacus Hamstrings

Rectus Femoris

Sartorius

Muscles of the medial compartment of the thigh (pectinius,

adductor longus, adductor brevis, gracilis)

Adductors Abductors

Adductor brevis Gluteus

medius

Adductor longus Gluteus

minimus

Adductor magnus & minimus

Pectineus

Gracilis

Obturator externus

Lateral Rotators Medial

Rotators

Obturators (internus & externus) Gluteus medius

Gemelli (superior & inferior) Gluteus minimus

Piriformis

Quadratus femoris

___________________________________________________________

HIP FLEXORS

________________________________________________________

GLUTEUS MAXIMUS

GLUTEUS MEDIUS

__________________________________________________________

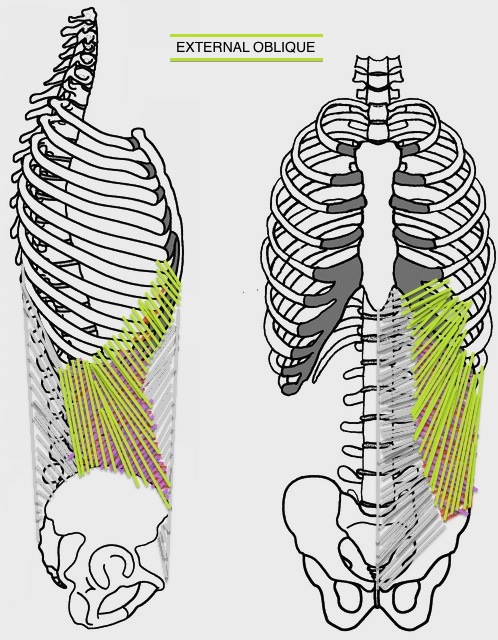

LATERAL ROTATORS (credit: www.iadms.org)

_____________________________________________________

ADDUCTORS

____________________________________________________

Due to the central location of the hips and pelvis in the

kinetic chain, imbalances in the strength and flexibility of the hip muscles

can result in misalignment and injury farther up and down the kinetic chain.

A great example of this is the effect of weak gluteal

muscles on the knee and foot. If gluteus

medius and gluteus minimus (our primary hip abductors) are weak, the femur will

tend to adduct and internally rotate. If

you follow this down the kinetic chain, the knee will fall into a “knock-kneed”

position and proper knee tracking will be disturbed, the foot will tend to pronate. The smaller leg muscles are not able to make

up for the weakness of the gluteal muscles and a number of injuries (IT band

syndrome, achilles tendionosis, plantar fasciitis, & shin splints) can

result along the lower kinetic chain.

Since over activity of the adductor muscles coupled with

weakness of the gluteal muscles is one of the most common imbalances that can

lead to injury lets look at a couple of exercises you can easily add to your

fitness routine to help prevent this imbalance.

The gluteal muscles are primarily hip extensors and

abductors. Exercises that involve

extending your leg behind you and lifting your leg to the side will target

these muscles. The tricky part,

especially in people who have trouble accessing these muscles, is making sure

the gluteal muscles are doing the work. Your

abdominals are the key to keeping your pelvis and spine stable during hip

extension work.

Although it looks quite simple, I would suggest starting

this exercise lifting your leg only.

Then progress by taking your opposite hand on to your abdominals while

you lift your leg. This is a great way

to provide some sensory feedback as to the stability of your spine and

pelvis. Your “hip-bones” (the bones you

feel protruding on the front of your pelvis) should stay in the same vertical

plane as your pubic bone to maintain neutral pelvis, and you should feel your

abdominals pulling in toward your spine.

You can then add abduction by maintain the height of your

leg and moving it away from the midline of your body. Again, try this with your opposite hand on

your abdominals to help police the stability of your spine and pelvis as well

as the depth of your abdominal contraction.

Training all of the muscles of the hip in a way that

balances strength and flexibility will not only prevent local injury but will

also help to maintain alignment and prevent injury along the whole length of

the kinetic chain.

Akuthota, V.A., Ferreiro, T.M. Fredericson, M. (2007) Core

stability exercise principles. Current

Sports Medicine Reports, 7(1), 39-44.

Geraci M.C. (1994) Rehabilitation of pelvis, hip and thigh

injuries in sports. Physical Medicine

& Rehabilitation Clinics of North America, 5, 157-73.

Geraci, M.C., Brown, W. (2005) Evidence-Based treatment of

hip and pelvic injuries in runners. Physical

Medicine & Rehabilitation Clinics of North America, 16, 711-747.

Lloyd-Smith, R., Clement, D.B., McKenzie, D.C., et.al.

(1995) A survey of overuse and traumatic hip and pelvis injuries in athletes. The Physician and Sportsmedicine, 13,

131-41.

Sciascia, A., Cromwell, R. (2012) Kinetic chain

rehabilitation: a theoretical framework. Rehabilitation

Research and Practice, 2012, 1-9.